conversation

WELCOME TO THE FUTURE

by DANIEL ARSHAM & VIVEK JAYARAM

Vivek Jayaram: So Daniel, you were born in Cleveland and raised in Miami. When did you first leave Miami?

Daniel Arsham: I left Miami in 1999.

Vivek: That was about 5 years before I moved here from New York. Why did you leave?

Daniel: To go to school in New York in fall of 1999.

Vivek: So you left to go to Cooper Union?

Daniel: Yes.

Vivek: When you left, do you remember anything about what was happening in the local art scene around here, in Miami. At that point, in 1999, I don't think I had even ever been to Miami in my life.

Daniel: There was not much at that point going on. I don't even know if Locust Projects was open. It may have been. I had done a couple of exhibitions with a place in Fort Lauderdale that was run by our professor. So when I left for NY a lot of that stuff hadn't been formed yet, like The House and all those other things that came later.

Vivek: Right. Then you came back to Miami from Cooper in like 2003? That makes sense, because I met you shortly after that, and you were done with Cooper and you were already showing with Emanuel, I think.

Daniel: So I was back and forth, and there was a period where I considered actually taking a year off school. It's great that I didn't, but I was back and forth. I was certainly in Miami in the summers, and it was around that time, I think it was maybe 2000, around 2000 that The House was started. So when I was in town, I was involved in that, in the formation of it and in the founding of it. And obviously, I was away at school during the first two years of that. But yeah, returned to Miami in 2003.

Vivek: Cool. Tell me a little bit about The House. What do you remember your first impressions of it being? Like who was involved in it and like what was happening there and where was it? My general recollection of the time was that everybody and every thing down here was kind of just emerging. A bubbling of talent.

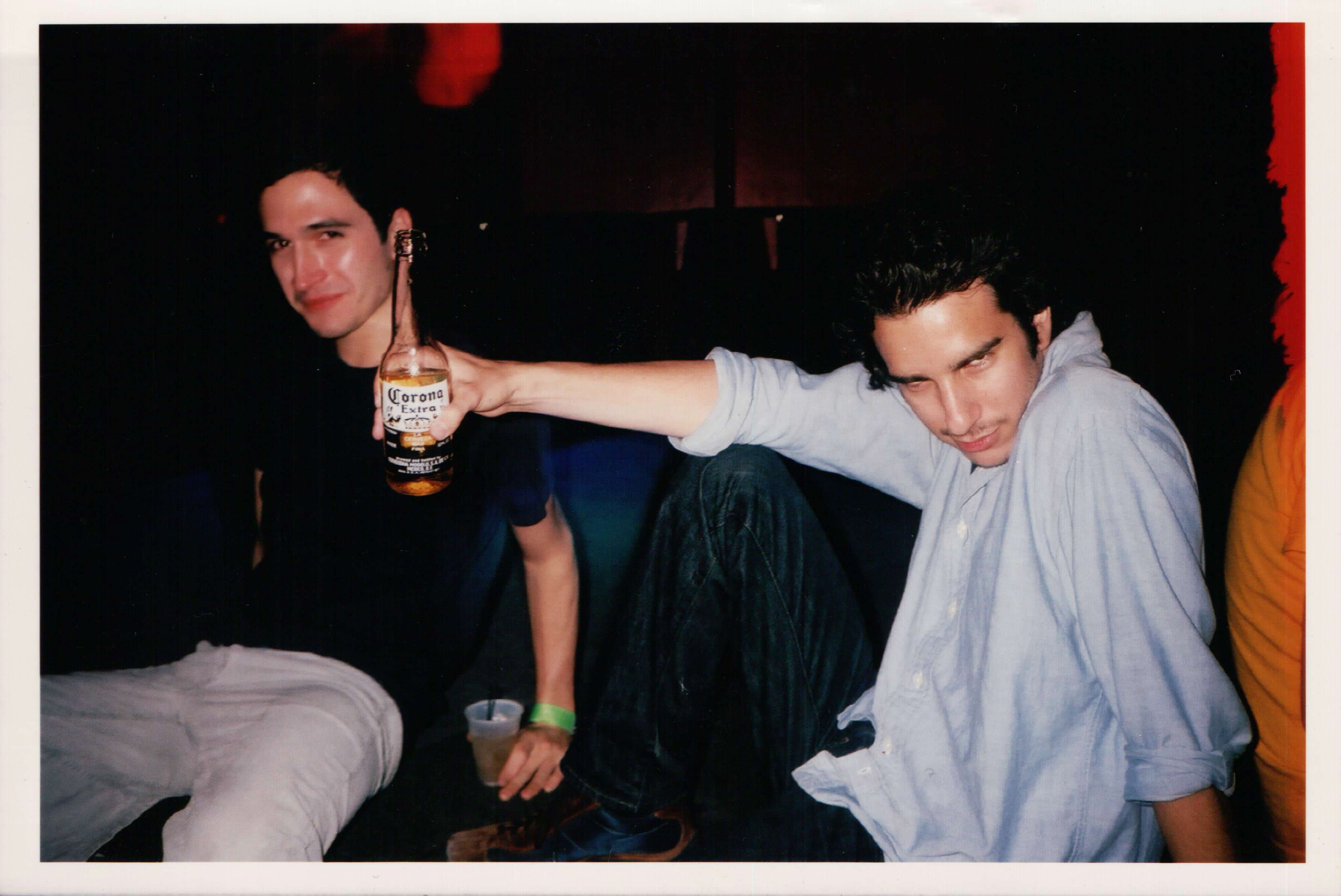

Daniel: The House was between 24th and 25th, one block east of Biscayne,in Edgewater. When we got it was a bit rundown. It was a white typical Miami bungalow-style house, that had a porch on the front of it that was enclosed, and we basically demolished all the walls on the ground floor and repainted the floors, making it look like what we thought a gallery looked like, and we started having exhibitions there and it became a place in once a month that we would have a big party in the backyard. We had real food and have beer and all that. And it was a gathering place for a lot of different people over that time.

Vivek: And it was also around that time, I guess around 2003 or so when you signed on with Emmanuel, right? With Perrotin. My best memories of Perrotin involved the art walks in Wynwood when all the galleries opened up I think one Saturday a month. That was a vibe.

Daniel: So I met Emmanuel in 2002, maybe. When I was back for Art Basel, and at that point we had an additional studio that was in the Design District that Craig Robins had given us.

Vivek: Yeah, I remember that. Craig was helping everybody.

Daniel: It's in a building that no longer exists, but it was basically on Northeast Second Avenue and like 39th Street. Yeah, we had the studio there and we met Emmanuel through a local collective.

Vivek: Okay. Did you know Craig Robins before you left to Cooper? Or was he somebody you met during the early Emanuel years?

Daniel: I had met him once when I was in high school, so I must have been, or maybe directly after I was probably 18 or 19 years old. I think there was like a talk that was given at another gallery that I was at. And I remember him asking me what we were up to. And there were a couple of other artists, I think Hernan Bas and Naomi already had a studio in the Design District. And so we asked him if he would do that for us too.

Vivek: Cool. And he ended up giving you space in Design District, right?

Daniel: Yeah, we had space there for multiple years.

Vivek: You and I ended up meeting probably in 2005 through Carolina. I remember the first time I met you I think was in Jenny Goldberg's backyard at that house in south Miami. I was asking you about art and you were asking me about constitutional law. I always thought that was hilarious. Not much has changed.

Daniel: Yeah, probably. I could see that.

Vivek: I think it was a party. I was playing tennis with Chris McLeod and then you, me and Chris were hanging out. When did you end up leaving for NYC?

Daniel: During all those years I effectively had a place in New York, so I would come back and forth. Some friends, Alex (Mustonen, Arsham’s partner in Snarkitecture) actually had this apartment that a bunch of people, I basically just had a bed in there. I started coming back more frequently in 2005.

Vivek: So this book is called Making Miami, and it tells a story of all of you guys, all the artists that were here during those years and how that group of artists really had an extraordinary impact on making the Miami we all see today. When you think back to those years in the early 2000s in Miami, why do you think that those years ended up producing that really interesting mix of creative people and what's your impression of that time?

Daniel: Yeah, I think it's a couple of different things that I can pinpoint. One is certainly, that was the moment that all of the magnet schools were starting to produce real talent. So New World, Dash certainly, and all of us were basically starting to graduate college at that point. We all knew each other. So that's one aspect of it. I think the magnet high schools graduating students that were going to a lot of significant art colleges whether it's RISD or Cooper, Pratt, all of those schools. And then the other thing I think was a combination of inexpensive rents being available in Miami. Everyone's sort of gathering in a very small neighborhood. Everyone lived between Edgewater and Wynwood basically. It was probably within a 10 square block radius. Most of the people I knew were living there.

Vivek: Yep. I've always felt that the art made in Miami feels so different than really anywhere else because of the mix of cultures here. That and Basel have made a huge difference.

Daniel: Then the thing that really set it off, I think was Art Basel coming there. This acted as a catalyst for other people from outside Miami to want to go there and see what was happening at the beginning of Basel. Before Basel, there weren’t the kind of parties and other things going on that we see every year nowadays. So before the fair arrived, people rarely visited art studios or engaged with contemporary art in that way in Miami. It’s all so different now.

conversation

WELCOME TO THE FUTURE

by DANIEL ARSHAM & VIVEK JAYARAM

Vivek Jayaram: So Daniel, you were born in Cleveland and raised in Miami. When did you first leave Miami?

Daniel Arsham: I left Miami in 1999.

Vivek: That was about 5 years before I moved here from New York. Why did you leave?

Daniel: To go to school in New York in fall of 1999.

Vivek: So you left to go to Cooper Union?

Daniel: Yes.

Vivek: When you left, do you remember anything about what was happening in the local art scene around here, in Miami. At that point, in 1999, I don't think I had even ever been to Miami in my life.

Daniel: There was not much at that point going on. I don't even know if Locust Projects was open. It may have been. I had done a couple of exhibitions with a place in Fort Lauderdale that was run by our professor. So when I left for NY a lot of that stuff hadn't been formed yet, like The House and all those other things that came later.

Vivek: Right. Then you came back to Miami from Cooper in like 2003? That makes sense, because I met you shortly after that, and you were done with Cooper and you were already showing with Emanuel, I think.

Daniel: So I was back and forth, and there was a period where I considered actually taking a year off school. It's great that I didn't, but I was back and forth. I was certainly in Miami in the summers, and it was around that time, I think it was maybe 2000, around 2000 that The House was started. So when I was in town, I was involved in that, in the formation of it and in the founding of it. And obviously, I was away at school during the first two years of that. But yeah, returned to Miami in 2003.

Vivek: Cool. Tell me a little bit about The House. What do you remember your first impressions of it being? Like who was involved in it and like what was happening there and where was it? My general recollection of the time was that everybody and every thing down here was kind of just emerging. A bubbling of talent.

Daniel: The House was between 24th and 25th, one block east of Biscayne,in Edgewater. When we got it was a bit rundown. It was a white typical Miami bungalow-style house, that had a porch on the front of it that was enclosed, and we basically demolished all the walls on the ground floor and repainted the floors, making it look like what we thought a gallery looked like, and we started having exhibitions there and it became a place in once a month that we would have a big party in the backyard. We had real food and have beer and all that. And it was a gathering place for a lot of different people over that time.

Vivek: And it was also around that time, I guess around 2003 or so when you signed on with Emmanuel, right? With Perrotin. My best memories of Perrotin involved the art walks in Wynwood when all the galleries opened up I think one Saturday a month. That was a vibe.

Daniel: So I met Emmanuel in 2002, maybe. When I was back for Art Basel, and at that point we had an additional studio that was in the Design District that Craig Robins had given us.

Vivek: Yeah, I remember that. Craig was helping everybody.

Daniel: It's in a building that no longer exists, but it was basically on Northeast Second Avenue and like 39th Street. Yeah, we had the studio there and we met Emmanuel through a local collective.

Vivek: Okay. Did you know Craig Robins before you left to Cooper? Or was he somebody you met during the early Emanuel years?

Daniel: I had met him once when I was in high school, so I must have been, or maybe directly after I was probably 18 or 19 years old. I think there was like a talk that was given at another gallery that I was at. And I remember him asking me what we were up to. And there were a couple of other artists, I think Hernan Bas and Naomi already had a studio in the Design District. And so we asked him if he would do that for us too.

Vivek: Cool. And he ended up giving you space in Design District, right?

Daniel: Yeah, we had space there for multiple years.

Vivek: You and I ended up meeting probably in 2005 through Carolina. I remember the first time I met you I think was in Jenny Goldberg's backyard at that house in south Miami. I was asking you about art and you were asking me about constitutional law. I always thought that was hilarious. Not much has changed.

Daniel: Yeah, probably. I could see that.

Vivek: I think it was a party. I was playing tennis with Chris McLeod and then you, me and Chris were hanging out. When did you end up leaving for NYC?

Daniel: During all those years I effectively had a place in New York, so I would come back and forth. Some friends, Alex (Mustonen, Arsham’s partner in Snarkitecture) actually had this apartment that a bunch of people, I basically just had a bed in there. I started coming back more frequently in 2005.

Vivek: So this book is called Making Miami, and it tells a story of all of you guys, all the artists that were here during those years and how that group of artists really had an extraordinary impact on making the Miami we all see today. When you think back to those years in the early 2000s in Miami, why do you think that those years ended up producing that really interesting mix of creative people and what's your impression of that time?

Daniel: Yeah, I think it's a couple of different things that I can pinpoint. One is certainly, that was the moment that all of the magnet schools were starting to produce real talent. So New World, Dash certainly, and all of us were basically starting to graduate college at that point. We all knew each other. So that's one aspect of it. I think the magnet high schools graduating students that were going to a lot of significant art colleges whether it's RISD or Cooper, Pratt, all of those schools. And then the other thing I think was a combination of inexpensive rents being available in Miami. Everyone's sort of gathering in a very small neighborhood. Everyone lived between Edgewater and Wynwood basically. It was probably within a 10 square block radius. Most of the people I knew were living there.

Vivek: Yep. I've always felt that the art made in Miami feels so different than really anywhere else because of the mix of cultures here. That and Basel have made a huge difference.

Daniel: Then the thing that really set it off, I think was Art Basel coming there. This acted as a catalyst for other people from outside Miami to want to go there and see what was happening at the beginning of Basel. Before Basel, there weren’t the kind of parties and other things going on that we see every year nowadays. So before the fair arrived, people rarely visited art studios or engaged with contemporary art in that way in Miami. It’s all so different now.

conversation

WELCOME TO THE FUTURE

by DANIEL ARSHAM & VIVEK JAYARAM

Vivek Jayaram: So Daniel, you were born in Cleveland and raised in Miami. When did you first leave Miami?

Daniel Arsham: I left Miami in 1999.

Vivek: That was about 5 years before I moved here from New York. Why did you leave?

Daniel: To go to school in New York in fall of 1999.

Vivek: So you left to go to Cooper Union?

Daniel: Yes.

Vivek: When you left, do you remember anything about what was happening in the local art scene around here, in Miami. At that point, in 1999, I don't think I had even ever been to Miami in my life.

Daniel: There was not much at that point going on. I don't even know if Locust Projects was open. It may have been. I had done a couple of exhibitions with a place in Fort Lauderdale that was run by our professor. So when I left for NY a lot of that stuff hadn't been formed yet, like The House and all those other things that came later.

Vivek: Right. Then you came back to Miami from Cooper in like 2003? That makes sense, because I met you shortly after that, and you were done with Cooper and you were already showing with Emanuel, I think.

Daniel: So I was back and forth, and there was a period where I considered actually taking a year off school. It's great that I didn't, but I was back and forth. I was certainly in Miami in the summers, and it was around that time, I think it was maybe 2000, around 2000 that The House was started. So when I was in town, I was involved in that, in the formation of it and in the founding of it. And obviously, I was away at school during the first two years of that. But yeah, returned to Miami in 2003.

Vivek: Cool. Tell me a little bit about The House. What do you remember your first impressions of it being? Like who was involved in it and like what was happening there and where was it? My general recollection of the time was that everybody and every thing down here was kind of just emerging. A bubbling of talent.

Daniel: The House was between 24th and 25th, one block east of Biscayne,in Edgewater. When we got it was a bit rundown. It was a white typical Miami bungalow-style house, that had a porch on the front of it that was enclosed, and we basically demolished all the walls on the ground floor and repainted the floors, making it look like what we thought a gallery looked like, and we started having exhibitions there and it became a place in once a month that we would have a big party in the backyard. We had real food and have beer and all that. And it was a gathering place for a lot of different people over that time.

Vivek: And it was also around that time, I guess around 2003 or so when you signed on with Emmanuel, right? With Perrotin. My best memories of Perrotin involved the art walks in Wynwood when all the galleries opened up I think one Saturday a month. That was a vibe.

Daniel: So I met Emmanuel in 2002, maybe. When I was back for Art Basel, and at that point we had an additional studio that was in the Design District that Craig Robins had given us.

Vivek: Yeah, I remember that. Craig was helping everybody.

Daniel: It's in a building that no longer exists, but it was basically on Northeast Second Avenue and like 39th Street. Yeah, we had the studio there and we met Emmanuel through a local collective.

Vivek: Okay. Did you know Craig Robins before you left to Cooper? Or was he somebody you met during the early Emanuel years?

Daniel: I had met him once when I was in high school, so I must have been, or maybe directly after I was probably 18 or 19 years old. I think there was like a talk that was given at another gallery that I was at. And I remember him asking me what we were up to. And there were a couple of other artists, I think Hernan Bas and Naomi already had a studio in the Design District. And so we asked him if he would do that for us too.

Vivek: Cool. And he ended up giving you space in Design District, right?

Daniel: Yeah, we had space there for multiple years.

Vivek: You and I ended up meeting probably in 2005 through Carolina. I remember the first time I met you I think was in Jenny Goldberg's backyard at that house in south Miami. I was asking you about art and you were asking me about constitutional law. I always thought that was hilarious. Not much has changed.

Daniel: Yeah, probably. I could see that.

Vivek: I think it was a party. I was playing tennis with Chris McLeod and then you, me and Chris were hanging out. When did you end up leaving for NYC?

Daniel: During all those years I effectively had a place in New York, so I would come back and forth. Some friends, Alex (Mustonen, Arsham’s partner in Snarkitecture) actually had this apartment that a bunch of people, I basically just had a bed in there. I started coming back more frequently in 2005.

Vivek: So this book is called Making Miami, and it tells a story of all of you guys, all the artists that were here during those years and how that group of artists really had an extraordinary impact on making the Miami we all see today. When you think back to those years in the early 2000s in Miami, why do you think that those years ended up producing that really interesting mix of creative people and what's your impression of that time?

Daniel: Yeah, I think it's a couple of different things that I can pinpoint. One is certainly, that was the moment that all of the magnet schools were starting to produce real talent. So New World, Dash certainly, and all of us were basically starting to graduate college at that point. We all knew each other. So that's one aspect of it. I think the magnet high schools graduating students that were going to a lot of significant art colleges whether it's RISD or Cooper, Pratt, all of those schools. And then the other thing I think was a combination of inexpensive rents being available in Miami. Everyone's sort of gathering in a very small neighborhood. Everyone lived between Edgewater and Wynwood basically. It was probably within a 10 square block radius. Most of the people I knew were living there.

Vivek: Yep. I've always felt that the art made in Miami feels so different than really anywhere else because of the mix of cultures here. That and Basel have made a huge difference.

Daniel: Then the thing that really set it off, I think was Art Basel coming there. This acted as a catalyst for other people from outside Miami to want to go there and see what was happening at the beginning of Basel. Before Basel, there weren’t the kind of parties and other things going on that we see every year nowadays. So before the fair arrived, people rarely visited art studios or engaged with contemporary art in that way in Miami. It’s all so different now.

conversation

EDGE ZONES & THE ART BASEL PHENOMENON

by CHARO OQUET & DAVID MARSH

Charo Oquet: In 2007, our second Zones Contemporary Art Fair took place at the World Arts Building on 2214 North Miami Avenue, where Edge Zone was located. It was a special time for us.

David Marsh: I am reflecting on the uniqueness of Edge Zones in the Wynwood Art District. It was a space that allowed artists complete freedom to express themselves creatively.

Charo: It was a massive undertaking with a 25,000 square feet of space spread across three floors, complete with a theater, bar, and even a ping pong table. By the time we moved from that building, we had built a total of 23 separate gallery spaces.

David: That's impressive! Creating a parallel art fair to Art Basel Miami must have been a monumental task.

Charo: As a Dominican Republic native with experience attending art fairs like ARCO in Spain, I was curious about how local artists would be included in the Art Basel phenomenon in Miami.

It became clear that local artists and the Miami art scene were relatively uninformed about the impact this would have. This realization sparked my interest in finding ways for the local community to participate in this event. In 2006, we launched our first Zones Art Fair, and in 2007, we organized our largest and most elaborate fair, featuring segments like Talks Zone and live music. We invited international curators. We not only provided local artists with affordable booth opportunities but also rented spaces to international galleries

We also allocated individual spaces to groups of artists from Puerto Rico, Basel Switzerland, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic.

David: What you did with Zones Art Fair was unique because it connected the art fair concept to the more discursive biennales. It provided a platform for emerging artists from marginalized countries. This allowed for some truly beautiful and genuine artistic experiences that you don't often find in other art fairs. Coming from Connecticut, I didn't have much exposure to art fairs before coming to Miami. Art Basel was my first experience when I was 19 and it was mind-blowing. Meeting you and being able to connect with collectors and more accomplished artists was a turning point for me. It propelled me to pursue a master's degree based on my ability to create and showcase my paintings in your space.

Charo: There was a vibrant energy in Miami where anything felt possible.

David: Back then, there was a chance to meet real collectors at events. I was a 20-year-old invited by Art Basel, showcasing my video projector art on the walls.

Charo: Miami wasn't prepared for the injection of art and visitors. It took a while for everyone including our local government figure out how to understand the phenomenon and support it financially.

David: Art Basel was where I first saw Basquiat paintings. I also learned about running a bar in an art gallery through Art Basel. The early art fairs shaped many things and have had a significant impact on my life.

Charo: Art Basel brought amazing art from all over the world, raising our standards and forcing us to develop. However, it also negatively affected local artists and galleries.

David: Despite the downsides, I believe there are more collectors as a result. I think the art fairs have played a significant role in attracting people to Miami. Over the years, visitors have come to realize how great our art scene is. This has resulted in the emergence of a new generation of young collectors who are actively supporting and collecting the work of local artists. Art Basel in Miami provided numerous opportunities for local artists like myself. While many of my friends felt the need to go to New York City, I stayed here and witnessed the positive impact the event had on our art scene.

Charo: Art Basel brought about a significant shift in the perception of art and collecting in Miami. While Miami already had a thriving art scene with local fairs and Latin American galleries, Art Basel introduced a whole new level of galleries and artists that elevated the city's status.

David: The consequences that have come out of it is that a lot of us make art for the market because the city has been shaped by the art market. It's not just museums. The museums here are not that important. It's the art market here that's the thing.

Charo: Edge Zones no longer produces the Zones Art Fair. Creating and maintaining an Art Fair year-round is challenging, especially with a small staff like ours. Looking back, it's amazing what we accomplished back then, but I can't do it now! Anyway, I think this was a good conversation. Thank you, David.

David: Hey, those are some of my best memories- I appreciate everything you accomplished.

conversation

EARLY DESIGN DISTRICT

by FRIENDSWITHYOU & SAM & TURY

Samuel Borkson: Hey, what's going on. This is Sam.

Arturo Sandoval III: And Tury here.

Sam: And together, we are FriendsWithYou. We were really lucky to be able to get a space in the Design District around 2007 / 2008. Craig Robins and Pharrell Williams set us up in the Melin building, and it was really, really major for us.

Tury: Yeah. Special time, new beginnings for us from, actually, I guess it was our first studio together.

Sam: Yeah. We'd been working from my tiny apartment and from Tury's house for years before that - we had started working at Tury's house in 2001 / 2002. So, this was our first really amazing moment together. And it kind of changed our whole trajectory and opened up our art career. The Design District is a really cool place because it brought people from all different kinds of businesses, like people from the entertainment and design world as well as the art world. They were all in and around the Design at that moment. So, it was cool to be near a bunch of other artists and friends and getting inspired from them as well as people coming to the studio and coming to the Design District because it was a pretty awesome moment in Miami's history, the development of that.

Tury: Yeah, and I think something that was unique about that zone too was the cross-pollination between everyone that was there. Not just the artists, but also the other even retailers and high-end furniture makers. And I guess Marni was there and Margiela, and I think that those brands and disciplines were also eye-opening to us as we were mixing it into our own art practice and applying that to what we were making. It was very interesting, and I feel like that was one of the magical, mystical ingredients to the Design District soup; it was such a mashup of everything at the same time.

Sam: Yeah, and all the artists had this crazy Palm Lot that we would get together at and have barbecues. Jason Hedges would cook crazy stuff, and all these guys like Daniel Arsham and Bhakti Baxter and Jay Hines and Jason Hedges and Nick Lobo, all welcomed me and Tury. It was a fun place. We were also really really inspired by Hernan Bas and Naomi Fisher, who were the people really making it at that time, and Bert Rodriguez, and all these guys and girls in Miami that were making pure and amazing art and recognizing the strange stuff we were doing, and coming to our weird installations that we were making by hand, and it was a magical moment. But there were so many amazing magical moments in the Design District at that time! Especially Rainbow City with Pharrell, when we took over the palm lot and made a crazy experiential concert almost, NERD performed, PAPER magazine was involved and America Online was sponsoring. It was just such a crazy memory of this interactive and very special installation we made. But it formed a lot of who and what we are today, so we're forever grateful for that opportunity.

Tury: Yeah, it's special. I think that's what's also amazing about Miami and the type of setting that Miami is, that it does allow for a lot of experimentation without a lot of high degrees of second-guessing what you're doing in comparison to other peers because there was such a small community, and it was very cohesive how people gave each other feedback, supported each other, and rinse and repeat, just keep experimenting, keep moving forward. I feel it was a very unique setting. I don't know. At least, for instance, right now in Downtown L.A. where we are, the nearest studio is miles away, and over there, it was walking distance. It was such a small, tight-knit community of makers, thinkers, and mischiefs, and not such a formal approach to artmaking. Everyone was almost seeing how far and experimental we could get with what we were doing. I don't think anyone was being very straightforward making traditional paintings or traditional sculpture. Everyone was really on the fringes of what could be perceived as art.

Sam: Yeah, and even all our friends, our best friends, like Jen Stark and Alvaro Ilizarbe, and Bhakti and Daniel. It was this whole crazy group of friends making crazy stuff and even fashion and designers. Our good friends like Pres Rodriguez and the kids that are making Andrew skate shop now, are connected to what that was. There's a great group of people that were (and still are) in Miami and creating in this time, and we feel really special to be part of Miami and the history and the Design District.

FOREWORD

By the beginning of the 21st Century, Miami had evolved from a

winter haven for northerners, past real estate speculation, sunny

beaches, art deco and cocaine cowboys into a serious contender

as the keystone of international trade and finance between North

and South America. Geographically located at the center, it had

become the place where the hemispheres converged and people came

to reinvent themselves and find a new future.

Heady stuff. But it’s hard to make a community when three quarters

of the population was born someplace else. What we needed were

organically Miami things to bind us to the place, and to each

other.

Making Miami chronicles how Miami joined around art and evolved

a culture that creates. The conversations in this book show the

perspective of some of the key figures in that evolution. They

catalog an awesome and small “d” democratic ambition that art

be general, accessible and authentic. And quality, because what

moves us is great painting or music, dance or writing.

Miami has been a cultural center for years. It has been at the core

of Latin music for decades, its book fair has long established

itself as one of the country's best and its film festival shows

"foreign" films to audiences who view them as culturally “local.” A

new generation of wealth created in Miami propelled entrepreneurs

who assembled significant art collections built on fortunes made

in real estate, cars, law, beer, finance and trade. The geography

and the collecting community caught the eye of Art Basel, which

risked a bet on Miami and its future, creating a commercial

success that exploded into a tipping point in the cultural history

of the place.

Making Miami puts the diversity and dynamism of Miami on full

display, and shows in clear, vivid color, that this place has

something special to offer.

I’m proud of the catalytic role played by Knight Foundation,

funding every major institution and hundreds of grassroots projects

and artists. Our community goal, wonderfully reflected in these

pages, was to make art general in Miami, borrowing from the last

paragraph of James Joyce’s “The Dead,” which read, in part, “Yes,

the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland.”

When the final chapter is written, we want it to be true that the

newspapers were right: art was general all over Miami.

No single person or group can take credit for the transformation

of the city’s cultural life but the Miami of today seems far

removed from the Miami of 20 years ago. Ultimately, that’s par

for the course for a city in a state of constant reinvention.

With every new wave of people that get sand in their shoes, this

community grows and changes. It is a place of creativity, a young

city, and far from finished.

prologue

ALBERTO IBARGÜEN - President, Knight Foundation.

VIVEK & CAROLINA JAYARAM.

A LOVE LETTER TO MIAMI

Outsiders have long underestimated Miami. Like many great beauties, these tropical shores have attracted countless suitors attempting to tame its mystery, only to find Miami continues to resist definition and logic. This isn’t a city for conformists.This is a city for visionaries and dreamers. And dreams, as we all know, defy logic; only revealing their meaning in circuitous and transcendental ways, and often much, much later.

So, what does it mean to love Miami and what does the story of Miami mean to us?

Throughout history, the myths of all great cities have been woven by their creatives. To try and understand what happened in Mesopotamia, ancient Rome or Machu Picchu, we look to what the artists left behind. Carved etchings on a cliffside, beaded costumes, oil lamp painted canvases hung down long dark corridors, oratories in the town square or songs and stories, pressed and printed then shared and stored away. Creative expression has illuminated life in any time and place, shedding light on what it felt like to be alive. It’s never the complete story but it is a powerful lens that future generations can look back through to connect to and deepen their humanity.

Artists are the centripetal force that center, catalyze, organize and enliven a city. They are the observers; interpreting how our time here will be remembered. And so, it isn’t at all surprising that the cities which remain rooted in our modern imaginations, that evolve to mythic stature and pulse in ways other cities do not, were teeming with artists who lived, loved, lost and worked to leave behind their unique imprints. But inexplicably, in their time, most artists have been undervalued. In fact, most will likely wield greater influence long after they are gone, when we want to make sense of a new dawn and better comprehend how we got here.

Modern Miami owes a great debt to the multi-disciplinary artists who have long come here - from those fleeing oppressive regimes to those seeking a tropical escape to those running from or to something new and different. This beach encircled thumb tip of humid extravagance has long attracted creative souls and the devoted groupies like us who wanted to be in their orbits.

One of us came to study law at the University of Miami, fleeing a post 9/11 New York City, and co-founding LegalArt with her classmate, Lara O’Neil in 2002. The other came to clerk for a federal judge, and within hours of arriving, found his way to Sweat Records, which ignited a longtime friendship and record label with Lolo Reskin. Together, we found ourselves in an arts community that was just officially taking shape and looked a lot like us: immigrants, misfits, dreamers. In fact, our own story began when we first met at the Miami Art Museum, now known as PAMM! At the time, cultural shapers were gaining ground, discovering and developing long-neglected neighborhoods, philanthropy was formalizing and world-class collectors were helping woo one “little known” art fair from the other side of the Atlantic that would soon take root and wend its way into nearly every crevice of Miami.

But the early aughts still belonged to the local artists and the community that nurtured and championed them. Funnily, we both came for legal gigs and over the years have each been lucky to work alongside many visionary artists, founders, entrepreneurs– what’s the difference anymore? It’s been miraculous and great fun to see how artists shaped Miami. We know this book and the many, many stories captured here, offers but one uniquely colorful kaleidoscope lens of a moment in time and in a place where it was all possible.

At a 2022 gathering at our home on Miami Beach, we heard a newly transplanted New Yorker remark, “was there anything here before we all got here?” Startled, but inspired, the two of us looked at each other, undoubtedly recalled the early days of our relationship, and shared an identical thought: “histories need to be told, or else they disappear forever.”

Here’s this one, we hope you enjoy it. We love you, Miami.

Vivek + Carolina

Miami Beach

September, 2023

prologue

.png&w=3840&q=75)

FOREWORD

By the beginning of the 21st Century, Miami had evolved from a

winter haven for northerners, past real estate speculation, sunny

beaches, art deco and cocaine cowboys into a serious contender

as the keystone of international trade and finance between North

and South America. Geographically located at the center, it had

become the place where the hemispheres converged and people came

to reinvent themselves and find a new future.

Heady stuff. But it’s hard to make a community when three quarters

of the population was born someplace else. What we needed were

organically Miami things to bind us to the place, and to each

other.

Making Miami chronicles how Miami joined around art and evolved

a culture that creates. The conversations in this book show the

perspective of some of the key figures in that evolution. They

catalog an awesome and small “d” democratic ambition that art

be general, accessible and authentic. And quality, because what

moves us is great painting or music, dance or writing.

Miami has been a cultural center for years. It has been at the core

of Latin music for decades, its book fair has long established

itself as one of the country's best and its film festival shows

"foreign" films to audiences who view them as culturally “local.” A

new generation of wealth created in Miami propelled entrepreneurs

who assembled significant art collections built on fortunes made

in real estate, cars, law, beer, finance and trade. The geography

and the collecting community caught the eye of Art Basel, which

risked a bet on Miami and its future, creating a commercial

success that exploded into a tipping point in the cultural history

of the place.

Making Miami puts the diversity and dynamism of Miami on full

display, and shows in clear, vivid color, that this place has

something special to offer.

I’m proud of the catalytic role played by Knight Foundation,

funding every major institution and hundreds of grassroots projects

and artists. Our community goal, wonderfully reflected in these

pages, was to make art general in Miami, borrowing from the last

paragraph of James Joyce’s “The Dead,” which read, in part, “Yes,

the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland.”

When the final chapter is written, we want it to be true that the

newspapers were right: art was general all over Miami.

No single person or group can take credit for the transformation

of the city’s cultural life but the Miami of today seems far

removed from the Miami of 20 years ago. Ultimately, that’s par

for the course for a city in a state of constant reinvention.

With every new wave of people that get sand in their shoes, this

community grows and changes. It is a place of creativity, a young

city, and far from finished.

prologue

ALBERTO IBARGÜEN - President, Knight Foundation.

VIVEK & CAROLINA JAYARAM.

A LOVE LETTER TO MIAMI

Outsiders have long underestimated Miami. Like many great beauties, these tropical shores have attracted countless suitors attempting to tame its mystery, only to find Miami continues to resist definition and logic. This isn’t a city for conformists.This is a city for visionaries and dreamers. And dreams, as we all know, defy logic; only revealing their meaning in circuitous and transcendental ways, and often much, much later.

So, what does it mean to love Miami and what does the story of Miami mean to us?

Throughout history, the myths of all great cities have been woven by their creatives. To try and understand what happened in Mesopotamia, ancient Rome or Machu Picchu, we look to what the artists left behind. Carved etchings on a cliffside, beaded costumes, oil lamp painted canvases hung down long dark corridors, oratories in the town square or songs and stories, pressed and printed then shared and stored away. Creative expression has illuminated life in any time and place, shedding light on what it felt like to be alive. It’s never the complete story but it is a powerful lens that future generations can look back through to connect to and deepen their humanity.

Artists are the centripetal force that center, catalyze, organize and enliven a city. They are the observers; interpreting how our time here will be remembered. And so, it isn’t at all surprising that the cities which remain rooted in our modern imaginations, that evolve to mythic stature and pulse in ways other cities do not, were teeming with artists who lived, loved, lost and worked to leave behind their unique imprints. But inexplicably, in their time, most artists have been undervalued. In fact, most will likely wield greater influence long after they are gone, when we want to make sense of a new dawn and better comprehend how we got here.

Modern Miami owes a great debt to the multi-disciplinary artists who have long come here - from those fleeing oppressive regimes to those seeking a tropical escape to those running from or to something new and different. This beach encircled thumb tip of humid extravagance has long attracted creative souls and the devoted groupies like us who wanted to be in their orbits.

One of us came to study law at the University of Miami, fleeing a post 9/11 New York City, and co-founding LegalArt with her classmate, Lara O’Neil in 2002. The other came to clerk for a federal judge, and within hours of arriving, found his way to Sweat Records, which ignited a longtime friendship and record label with Lolo Reskin. Together, we found ourselves in an arts community that was just officially taking shape and looked a lot like us: immigrants, misfits, dreamers. In fact, our own story began when we first met at the Miami Art Museum, now known as PAMM! At the time, cultural shapers were gaining ground, discovering and developing long-neglected neighborhoods, philanthropy was formalizing and world-class collectors were helping woo one “little known” art fair from the other side of the Atlantic that would soon take root and wend its way into nearly every crevice of Miami.

But the early aughts still belonged to the local artists and the community that nurtured and championed them. Funnily, we both came for legal gigs and over the years have each been lucky to work alongside many visionary artists, founders, entrepreneurs– what’s the difference anymore? It’s been miraculous and great fun to see how artists shaped Miami. We know this book and the many, many stories captured here, offers but one uniquely colorful kaleidoscope lens of a moment in time and in a place where it was all possible.

At a 2022 gathering at our home on Miami Beach, we heard a newly transplanted New Yorker remark, “was there anything here before we all got here?” Startled, but inspired, the two of us looked at each other, undoubtedly recalled the early days of our relationship, and shared an identical thought: “histories need to be told, or else they disappear forever.”

Here’s this one, we hope you enjoy it. We love you, Miami.

Vivek + Carolina

Miami Beach

September, 2023

prologue

.png&w=3840&q=75)

prologue

.png&w=3840&q=75)

MILESTONES IN MIAMI'S COMING OF AGE SAGA

by ELISA TURNER

January 10, 1999 It’s one year before the millennium. Three years before the first Art Basel Miami Beach finally arrives. Already Miami’s art scene percolates with ambition, I write in “Visually on the Verge: With Tropical Cliches Safely in the Past, Could South Florida’s Art Future Be Something Great?” The fair Art Miami attracts collectors and curators, among them New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Lowery Sims. She tells me, “Obviously Miami is a hot scene. It’s very strong in Latin American art, and the visual arts in general. I’m coming down to see how it all goes together.” In town is Art Basel spokesman Samuel Keller, surely because Art Basel plans to stage a local event, possibly to coincide with a future Art Miami. “We are in a crossover time, and Miami is a crossover place,” he says.

George Sanchez declares these days “the most happening art week in Miami.” Area artists, collectors, dealers and others credit the efforts of MoCA, MAM, the Rubell Family Collection and FIU in particular with ratcheting up the visual arts bar. However, Fred Snitzer tells me, “I think the problem remains that we are lacking an enthusiastic audience that recognizes what the outside recognizes, that Miami is a great cultural mix.” Artists generate events feeding upon Art Miami’s global and local synergy. Compared to museums hosting big-budget shows or private collectors acquiring internationally known works, artists’ efforts may seem modest. But they are critical to the community’s creative future. Sanchez devises a massive installation recalling controversial times in South Florida history, the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Tom Downs curates a video and film screening by young, international artists for The Wolfsonian-FIU. Robert Chambers is in talks with New York’s Mexican Cultural Institute to establish links between artists in Mexico and Miami. “If you go out and approach people,things start to happen,” says Chambers.

January 30, 2000 This weekend marks a milestone in our coming of age saga. It demonstrates a clear desire for innovation in the visual arts. There are fine shows of art across greater Miami in private and public settings, including Martin Z. Margulies’s newly installed contemporary photography collection on Northwest 27th St. In “Artists Bond in Doomed Building,” I describe abundant buzz about an unprecedented gathering of new, site-specific work by 44 Miami artists in Departing Perspectives, curated by Fred Snitzer, at the former Espirito Santo Bank building on Brickell Ave. To Dennis Scholl, it’s “a defining moment for Miami, showing the community how many excellent working artists there are here. I got a chill walking up and down those floors.” Among the artists are Hernan Bas, Carol Brown, María Martínez-Cañas,Robert Chambers, Marissa Telleria Diez, Robert Huff, Karen Rifas, Lydia Rubio, Rubén Torres-Llorca, Purvis Young, TM Sisters, Eugenia Vargas, and Annie Wharton. On display are striking collaborations by Bhakti Baxter, Julian Picaza, Jay Hines and also by Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt. Working feverishly for five days, established artists alongside ambitious high-school and college art students transform eight floors of the soon-to-be demolished building. An estimated 2,400 visitors attend, including Art in America editor Elizabeth C. Baker and author Brian Antoni. Activity animating the doomed bank tower ignites a spirit of community among artists and audiences. “It feels tome like the high after Christo and Jeanne-Claude,” Rifas marvels.

August 6, 2000 Cultivated Under the Sun, the Miami-Dade Public Library’s look at 30 years of South Florida art, is curated by librarian Barbara Young and artists Carol Brown and César Trasobares. Young contemplates the late Fernando Garcia’s green and pink maps of Miami in this show. They resemble a patchwork quilt, created in an adventurous 1980s community project, becoming a witty metaphor for Miami, where people re-invent themselves, yet find they are still attached to reminders of previous homes. The trio, as I explain in “Past, Present and Future, As Seen by‘Cultivated’ Curators,” speak about how Miami’s art scene has dramatically evolved, recalling when—in the absence of serious museum attention—artists were nurtured by inventive, low-budget programs at the library and North Miami’s Center for Contemporary Art, which preceded Museum of Contemporary Art.

October 19, 2000 Barbara Young and Helen M. Kohen discuss a visual arts archive to document greater Miami’s art scene from the postwar years to the present. It’s time to recognize the years of contributions that artists, collectors, and their supporters have made to build Miami into an international cultural center, says Kohen, the Miami Herald’s art critic from 1979-95. “These days depend on those days,” she emphasizes. The archive is tentatively called the Vasari Project, after 16th Century Italian artist and writer Giorgio Vasari, admired for his artist biographies, I write in “Growth Spurts, Growing Pains, Flocks of Kitsch: What’s Next?” Yet, while we live in a subtropical paradise, plans for a county-wide show, Flamingos in Paradise, sound more like a growing pain than a spurt. Modeled after the widely publicized Cows on Parade, artist-decorated sculptures of cows in Chicago, it resonates with tired, copycat thinking.

November 5, 2000 At Miami Art Museum, Edouard Duval-Carrié’s Migrations is a tour de force mix of painting and sculpture wrought with imaginative references to sacred arts of Haitian Vodou. Reminiscent of a Vodou temple, Migrations is perfumed with lilies strewn on the floor and fraught with rococo curves of crumbling French colonial architecture. It probes complex African, American and European strands interlacing Haitian culture and history, I write in “Wall of Vodou.” Rendered here are painted panels including a faux marble relief recalling a Roman Catholic altarpiece. In one panel, a tropical forests molders while in another a tattooed goddess dances in a South Beach strip joint. They deliver bittersweet stories of a besieged country, represented by rural spirits migrating into new urban contexts. The spirits are testaments to the fluid energies of Vodou, which Haitian-born Duval-Carrie has long admired. He calls Vodou, with its syncretic assortment of Yoruba, Kongo, and Roman Catholic deities, “a guerrilla religion.” The show speaks volumes to Miami’s community shaped by Haitian and Caribbean immigrants.

September 9, 2001 Artists of The House, one of Miami's newest art venues, have a new home as curators of The House at MOCA. Director Bonnie Clearwater took a risk by collaborating with young artists in the midst of their own art education. Yet Martin Oppel, 24; Bhakti Mar Baxter, 21; and Tao Rey, 23, have elicited some admirable experimental work from peers in group shows they've orchestrated since December in their own home. Within their down-at-the-heels house in Edgewater, photography, video and installation art they've presented can move wildly from provocative to tedious. But there's an openness here not found in more structured venues. Not a new concept—think back nearly three decades to the collaborative project Womanhouse in Los Angeles. In Miami, The House signals an independent-minded artist community defining its own space for risk-taking. It seems the most recent manifestation of such initiative, in synch with artist Eugenia Vargas's shows in her home and the artist-led Locust Projects in a remodeled warehouse.Still, it was a challenge moving their curatorial style to a museum, Oppel admits. The intimate, casual spirit of a House show has been diminished, but there's still plenty of ambitious work to see, including memorable work by Baxter and Frances Trombly. Baxter created an ethereal web of strings evoking geometric grace in Sol LeWitt drawings. Trombly’s art recalls Rebecca Horn's mechanized sculptures of machines lacking an obvious function as well as the push and pull in personal relationships.

December 23, 2001 Bringing together work by 60 artists, Robert Chambers curates globe>Miami>island for the Bass Museum. I write in “Global Perspective” that more than a few works evoke imaginative places of rising dreams and desires, also notions about nurturing, regeneration and birth. It seems wonderfully apt for an event holding up a mirror—occasionally a wacky funhouse mirror—to an arts scene stepping out of its once-insular-as-an-island past to a more visible, if not global, stage. Amy Cappellazzo notes in her catalog essay that this exhibit encircles several generations of Miami artists, ranging from Purvis Young,Robert Huff, Robert Thiele, and Karen Rifas, who worked or taught here when Miami was considered nothing more than a brain-fried backwater by New York tastemakers, to the current crop twenty-something artists like Naomi Fisher, Gean Moreno and Cooper,whose work has attracted critical attention both here and beyond.In between these generations are those born in Cuba but raised in Miami, like César Trasobares and Pablo Cano, as well as others who came here later from Cuba like Glexis Novoa and José Bedia.The show itself does have flaws, especially in the muddled, chaotic beginning. Some artists aren’t represented by their most compelling works. Still, the new generation of Miami artists leaves you with surprising memories, like the glimmering 35mm slides projected on a hemispheric form by Kevin Arrow and Norberto Rodriguez’s The End, a sound piece filling the Bass elevator with hilariously triumphant chords from the end of famous movie soundtracks. In these endings are tantalizing beginnings.

April 27, 2003 It’s as if Miami has become these visionary artists’ playroom, a big city deserving big toys and dreams. Their latest living-large toy is a festive house of cards--perhaps about to collapse but perhaps not—built for Miami Art Museum. Working in their trademark and moderately gigantic mode, artists Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt have already caused a child’s peppermint-red block of the letter M to tower four stories high near the Miami River. This is the M outdoor sculpture at the Riverwalk Metromover station downtown. At MAM, their house of cards is a 12-foot high mansion of make-believe, I write in “Card Sharks. ”Surrounding it is a wooden scaffold, suggesting a place that, like Miami, is not yet finished. It’s part of their installation A Place in the World, lit with the lights of a street carnival illuminating a city plaza. Here, barely two-feet tall figures gather around the house of cards, one scaling a ladder, the other reclined in dreamy sleep. Recorded sounds of planes landing and departing and other jangly residues of traffic coming and going disrupt the reflective mood. “This is about excavating our own memories,” says Behar. “We find that we do have things in common, and they take the form of games and toys.” Charged memories nestle within this classic house of cards, cunning and precarious. In the case of collapse, “we say, ‘let’s try again,’ he affirms. “Now it’s realized. So it was possible.”

January 19, 2004 She’s the warrior maiden who collects machetes and British designer mini-skirts. He’s the skinny boy searching for the perfect cameo pin to wear with his Jill Stuart for Puma shoes. And as close friends and classmates trained in art programs in Miami-Dade County public schools, both Naomi Fisher and Hernan Bas are climbing the charts at a red-hot pace, winning praise and purchases from collectors around the art world, I write in “Amazing Journey—Naomi Fisher, Hernan Bas Connect in Life and Art.” Fisher’s fiercely beguiling blood-colored drawings of women were tapped for the inaugural show in 2002 at the Palais de Tokyo, the new contemporary art museum in Paris, and were just purchased for a prominent foundation in Essen, Germany. Bas will show his delicate, shadowy paintings of waifish boys on risky adventures at London’s cutting-edge Victoria Miro gallery and at the 2004 biennial of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. They met in high school creative writing class at New World School of the Arts and now share a studio in Miami Design District. In conversation,they seem like artistic soulmates. They are blood relatives via their shared DNA for art and fashion, Miami-style.

February 29, 2004 On a cool December evening in Miami Beach, Art Basel Miami Beach director Samuel Keller takes a break from exclusive SoBe parties to pocket an orange served up from a jet ski trailer parked in front of Free Spirits Sports Café, a deliciously seedy bar transformed into an impromptu art salon. “Wonderful. We’ll get a lot of vitamins,” Keller nods to Raymond Saá, who had tossed him the orange. With former New World School of the Arts classmate Michael Loveland, Saá had retrofitted an old jet ski trailer to make a street cart for pushing fruit and art during Art Basel Miami Beach. Grapefruit and oranges sell for $1 each. Art by Saá and Loveland cost hundreds of dollars. Keller had come to this street corner and bar for a tonic stronger than vitamins, I write in “Way Outside the Galleries.” He found that something in the can-do qualities of Miami artists, still on display this month and next in a loose network of artist-run spaces in the Design District, Wynwood, and Edgewater neighborhoods.

June 11, 2004 The House in Edgewater, a ramshackle house-cum-art space boasting an airy porch and open-minded atmosphere, is going down for the count. Its last hurrah is tonight, with a one-night-only exhibit in which several hundred artists have been invited to participate. Since opening in 2000 as a spirited venue run by its live-in artists to showcase themselves and others, it has been a catalyst for Miami’s youthfully expansive art scene. “We’re asking people to leave the work, and all of that will go down with The House,” says current tenant Daniel Arsham. For the moment, The House is a two-story 1930 Edward Hopper-esque survivor on a weedy block giving way to brisk development, I write in “Artists Gather Before the Wrecking Ball Hits.” It’s slated for demolition once the lease Arsham shares with artists Bhakti Baxter, Martin Oppel and Tao Rey expires Tuesday. For tonight, Arsham envisions ephemeral work placed inside and outside, as offerings to the energy The House generated. “It’s been an easy place to show and to make things happen in,” says Arsham.

* In the 1980s, award-winning art critic and journalist Elisa Turner began writing for ARTnews magazine as Miami correspondent and for the Miami Herald. From 1995 to 2007, she was the newspaper’s primary art critic, with international assignments to Havana, Haiti, Venice Biennial, and Art Basel. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications. These edited and condensed stories are culled from her personal Miami Herald archives. She is at work on a book drawn from those archives,"Miami’s Cultural Renaissance: Art Made It Happen".

prologue

.png&w=3840&q=75)

MILESTONES IN MIAMI'S COMING OF AGE SAGA

by ELISA TURNER

January 10, 1999 It’s one year before the millennium. Three years before the first Art Basel Miami Beach finally arrives. Already Miami’s art scene percolates with ambition, I write in “Visually on the Verge: With Tropical Cliches Safely in the Past, Could South Florida’s Art Future Be Something Great?” The fair Art Miami attracts collectors and curators, among them New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Lowery Sims. She tells me, “Obviously Miami is a hot scene. It’s very strong in Latin American art, and the visual arts in general. I’m coming down to see how it all goes together.” In town is Art Basel spokesman Samuel Keller, surely because Art Basel plans to stage a local event, possibly to coincide with a future Art Miami. “We are in a crossover time, and Miami is a crossover place,” he says.

George Sanchez declares these days “the most happening art week in Miami.” Area artists, collectors, dealers and others credit the efforts of MoCA, MAM, the Rubell Family Collection and FIU in particular with ratcheting up the visual arts bar. However, Fred Snitzer tells me, “I think the problem remains that we are lacking an enthusiastic audience that recognizes what the outside recognizes, that Miami is a great cultural mix.” Artists generate events feeding upon Art Miami’s global and local synergy. Compared to museums hosting big-budget shows or private collectors acquiring internationally known works, artists’ efforts may seem modest. But they are critical to the community’s creative future. Sanchez devises a massive installation recalling controversial times in South Florida history, the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Tom Downs curates a video and film screening by young, international artists for The Wolfsonian-FIU. Robert Chambers is in talks with New York’s Mexican Cultural Institute to establish links between artists in Mexico and Miami. “If you go out and approach people,things start to happen,” says Chambers.

January 30, 2000 This weekend marks a milestone in our coming of age saga. It demonstrates a clear desire for innovation in the visual arts. There are fine shows of art across greater Miami in private and public settings, including Martin Z. Margulies’s newly installed contemporary photography collection on Northwest 27th St. In “Artists Bond in Doomed Building,” I describe abundant buzz about an unprecedented gathering of new, site-specific work by 44 Miami artists in Departing Perspectives, curated by Fred Snitzer, at the former Espirito Santo Bank building on Brickell Ave. To Dennis Scholl, it’s “a defining moment for Miami, showing the community how many excellent working artists there are here. I got a chill walking up and down those floors.” Among the artists are Hernan Bas, Carol Brown, María Martínez-Cañas,Robert Chambers, Marissa Telleria Diez, Robert Huff, Karen Rifas, Lydia Rubio, Rubén Torres-Llorca, Purvis Young, TM Sisters, Eugenia Vargas, and Annie Wharton. On display are striking collaborations by Bhakti Baxter, Julian Picaza, Jay Hines and also by Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt. Working feverishly for five days, established artists alongside ambitious high-school and college art students transform eight floors of the soon-to-be demolished building. An estimated 2,400 visitors attend, including Art in America editor Elizabeth C. Baker and author Brian Antoni. Activity animating the doomed bank tower ignites a spirit of community among artists and audiences. “It feels tome like the high after Christo and Jeanne-Claude,” Rifas marvels.

August 6, 2000 Cultivated Under the Sun, the Miami-Dade Public Library’s look at 30 years of South Florida art, is curated by librarian Barbara Young and artists Carol Brown and César Trasobares. Young contemplates the late Fernando Garcia’s green and pink maps of Miami in this show. They resemble a patchwork quilt, created in an adventurous 1980s community project, becoming a witty metaphor for Miami, where people re-invent themselves, yet find they are still attached to reminders of previous homes. The trio, as I explain in “Past, Present and Future, As Seen by‘Cultivated’ Curators,” speak about how Miami’s art scene has dramatically evolved, recalling when—in the absence of serious museum attention—artists were nurtured by inventive, low-budget programs at the library and North Miami’s Center for Contemporary Art, which preceded Museum of Contemporary Art.

October 19, 2000 Barbara Young and Helen M. Kohen discuss a visual arts archive to document greater Miami’s art scene from the postwar years to the present. It’s time to recognize the years of contributions that artists, collectors, and their supporters have made to build Miami into an international cultural center, says Kohen, the Miami Herald’s art critic from 1979-95. “These days depend on those days,” she emphasizes. The archive is tentatively called the Vasari Project, after 16th Century Italian artist and writer Giorgio Vasari, admired for his artist biographies, I write in “Growth Spurts, Growing Pains, Flocks of Kitsch: What’s Next?” Yet, while we live in a subtropical paradise, plans for a county-wide show, Flamingos in Paradise, sound more like a growing pain than a spurt. Modeled after the widely publicized Cows on Parade, artist-decorated sculptures of cows in Chicago, it resonates with tired, copycat thinking.

November 5, 2000 At Miami Art Museum, Edouard Duval-Carrié’s Migrations is a tour de force mix of painting and sculpture wrought with imaginative references to sacred arts of Haitian Vodou. Reminiscent of a Vodou temple, Migrations is perfumed with lilies strewn on the floor and fraught with rococo curves of crumbling French colonial architecture. It probes complex African, American and European strands interlacing Haitian culture and history, I write in “Wall of Vodou.” Rendered here are painted panels including a faux marble relief recalling a Roman Catholic altarpiece. In one panel, a tropical forests molders while in another a tattooed goddess dances in a South Beach strip joint. They deliver bittersweet stories of a besieged country, represented by rural spirits migrating into new urban contexts. The spirits are testaments to the fluid energies of Vodou, which Haitian-born Duval-Carrie has long admired. He calls Vodou, with its syncretic assortment of Yoruba, Kongo, and Roman Catholic deities, “a guerrilla religion.” The show speaks volumes to Miami’s community shaped by Haitian and Caribbean immigrants.

September 9, 2001 Artists of The House, one of Miami's newest art venues, have a new home as curators of The House at MOCA. Director Bonnie Clearwater took a risk by collaborating with young artists in the midst of their own art education. Yet Martin Oppel, 24; Bhakti Mar Baxter, 21; and Tao Rey, 23, have elicited some admirable experimental work from peers in group shows they've orchestrated since December in their own home. Within their down-at-the-heels house in Edgewater, photography, video and installation art they've presented can move wildly from provocative to tedious. But there's an openness here not found in more structured venues. Not a new concept—think back nearly three decades to the collaborative project Womanhouse in Los Angeles. In Miami, The House signals an independent-minded artist community defining its own space for risk-taking. It seems the most recent manifestation of such initiative, in synch with artist Eugenia Vargas's shows in her home and the artist-led Locust Projects in a remodeled warehouse.Still, it was a challenge moving their curatorial style to a museum, Oppel admits. The intimate, casual spirit of a House show has been diminished, but there's still plenty of ambitious work to see, including memorable work by Baxter and Frances Trombly. Baxter created an ethereal web of strings evoking geometric grace in Sol LeWitt drawings. Trombly’s art recalls Rebecca Horn's mechanized sculptures of machines lacking an obvious function as well as the push and pull in personal relationships.

December 23, 2001 Bringing together work by 60 artists, Robert Chambers curates globe>Miami>island for the Bass Museum. I write in “Global Perspective” that more than a few works evoke imaginative places of rising dreams and desires, also notions about nurturing, regeneration and birth. It seems wonderfully apt for an event holding up a mirror—occasionally a wacky funhouse mirror—to an arts scene stepping out of its once-insular-as-an-island past to a more visible, if not global, stage. Amy Cappellazzo notes in her catalog essay that this exhibit encircles several generations of Miami artists, ranging from Purvis Young,Robert Huff, Robert Thiele, and Karen Rifas, who worked or taught here when Miami was considered nothing more than a brain-fried backwater by New York tastemakers, to the current crop twenty-something artists like Naomi Fisher, Gean Moreno and Cooper,whose work has attracted critical attention both here and beyond.In between these generations are those born in Cuba but raised in Miami, like César Trasobares and Pablo Cano, as well as others who came here later from Cuba like Glexis Novoa and José Bedia.The show itself does have flaws, especially in the muddled, chaotic beginning. Some artists aren’t represented by their most compelling works. Still, the new generation of Miami artists leaves you with surprising memories, like the glimmering 35mm slides projected on a hemispheric form by Kevin Arrow and Norberto Rodriguez’s The End, a sound piece filling the Bass elevator with hilariously triumphant chords from the end of famous movie soundtracks. In these endings are tantalizing beginnings.

April 27, 2003 It’s as if Miami has become these visionary artists’ playroom, a big city deserving big toys and dreams. Their latest living-large toy is a festive house of cards--perhaps about to collapse but perhaps not—built for Miami Art Museum. Working in their trademark and moderately gigantic mode, artists Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt have already caused a child’s peppermint-red block of the letter M to tower four stories high near the Miami River. This is the M outdoor sculpture at the Riverwalk Metromover station downtown. At MAM, their house of cards is a 12-foot high mansion of make-believe, I write in “Card Sharks. ”Surrounding it is a wooden scaffold, suggesting a place that, like Miami, is not yet finished. It’s part of their installation A Place in the World, lit with the lights of a street carnival illuminating a city plaza. Here, barely two-feet tall figures gather around the house of cards, one scaling a ladder, the other reclined in dreamy sleep. Recorded sounds of planes landing and departing and other jangly residues of traffic coming and going disrupt the reflective mood. “This is about excavating our own memories,” says Behar. “We find that we do have things in common, and they take the form of games and toys.” Charged memories nestle within this classic house of cards, cunning and precarious. In the case of collapse, “we say, ‘let’s try again,’ he affirms. “Now it’s realized. So it was possible.”

January 19, 2004 She’s the warrior maiden who collects machetes and British designer mini-skirts. He’s the skinny boy searching for the perfect cameo pin to wear with his Jill Stuart for Puma shoes. And as close friends and classmates trained in art programs in Miami-Dade County public schools, both Naomi Fisher and Hernan Bas are climbing the charts at a red-hot pace, winning praise and purchases from collectors around the art world, I write in “Amazing Journey—Naomi Fisher, Hernan Bas Connect in Life and Art.” Fisher’s fiercely beguiling blood-colored drawings of women were tapped for the inaugural show in 2002 at the Palais de Tokyo, the new contemporary art museum in Paris, and were just purchased for a prominent foundation in Essen, Germany. Bas will show his delicate, shadowy paintings of waifish boys on risky adventures at London’s cutting-edge Victoria Miro gallery and at the 2004 biennial of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. They met in high school creative writing class at New World School of the Arts and now share a studio in Miami Design District. In conversation,they seem like artistic soulmates. They are blood relatives via their shared DNA for art and fashion, Miami-style.

February 29, 2004 On a cool December evening in Miami Beach, Art Basel Miami Beach director Samuel Keller takes a break from exclusive SoBe parties to pocket an orange served up from a jet ski trailer parked in front of Free Spirits Sports Café, a deliciously seedy bar transformed into an impromptu art salon. “Wonderful. We’ll get a lot of vitamins,” Keller nods to Raymond Saá, who had tossed him the orange. With former New World School of the Arts classmate Michael Loveland, Saá had retrofitted an old jet ski trailer to make a street cart for pushing fruit and art during Art Basel Miami Beach. Grapefruit and oranges sell for $1 each. Art by Saá and Loveland cost hundreds of dollars. Keller had come to this street corner and bar for a tonic stronger than vitamins, I write in “Way Outside the Galleries.” He found that something in the can-do qualities of Miami artists, still on display this month and next in a loose network of artist-run spaces in the Design District, Wynwood, and Edgewater neighborhoods.

June 11, 2004 The House in Edgewater, a ramshackle house-cum-art space boasting an airy porch and open-minded atmosphere, is going down for the count. Its last hurrah is tonight, with a one-night-only exhibit in which several hundred artists have been invited to participate. Since opening in 2000 as a spirited venue run by its live-in artists to showcase themselves and others, it has been a catalyst for Miami’s youthfully expansive art scene. “We’re asking people to leave the work, and all of that will go down with The House,” says current tenant Daniel Arsham. For the moment, The House is a two-story 1930 Edward Hopper-esque survivor on a weedy block giving way to brisk development, I write in “Artists Gather Before the Wrecking Ball Hits.” It’s slated for demolition once the lease Arsham shares with artists Bhakti Baxter, Martin Oppel and Tao Rey expires Tuesday. For tonight, Arsham envisions ephemeral work placed inside and outside, as offerings to the energy The House generated. “It’s been an easy place to show and to make things happen in,” says Arsham.

* In the 1980s, award-winning art critic and journalist Elisa Turner began writing for ARTnews magazine as Miami correspondent and for the Miami Herald. From 1995 to 2007, she was the newspaper’s primary art critic, with international assignments to Havana, Haiti, Venice Biennial, and Art Basel. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications. These edited and condensed stories are culled from her personal Miami Herald archives. She is at work on a book drawn from those archives,"Miami’s Cultural Renaissance: Art Made It Happen".

prologue

MAKING MIAMI

by KATERINA LLANES - Curator and Program Manager at Jayaram

In my role as Curator for Jayaram, I was thrilled to be a part of conceiving this book, which aims to capture the collective energy of Miami’s contemporary art scene during a pivotal time in our city’s history. I sat and reflected on my own experience as a Miami millennial native, born to Cuban parents and raised in Kendall. In my youth, Miami felt too small for me, and I left the minute I turned 18 for college and then NYC. It wasn’t until I met Naomi Fisher in 2007 that Miami’s secret artworld opened up to me. Naomi was an art star running BFI (Bas Fisher Invitational) out of the Buena Vista building in the Design District. Always a welcoming spirit, Naomi invited me to EVERYTHING and before long, I was tapped in and turned on. I would go on to work at BFI for years, both at the Buena Vista and later at the Downtown ArtHouse that we shared with the TM Sisters, Turn-Based Press and Dimensions Variable. In 2013, I was hired by the Miami Art Museum to run the Time-Based Art program in their new Herzog and de Meuron building, renamed the Pérez Art Museum, or PAMM. These experiences solidified my career as a curator and my new-found love for my hometown.

Making Miami is an archive of voices from the Miami art community in the early 2000s. The book comprises over 40 conversations, images and ephemera from influential artists, curators, collectors, gallerists, musicians and writers, each telling their story of how the Magic City was transformed by a compendium of dynamic creative forces. As the curatorial concept, and to ensure this book truly represented its community, we invited one person and asked them to choose their conversation partner. That way, the connection was truly authentic.

As Miami has evolved into a cultural mecca, we felt it necessary to share these stories, so they are not forgotten, and moreover, that they are told first-hand by those who shaped it. The book is a companion piece to the exhibition on view in the Design District during Miami Art Week 2023, which focuses on non-profit artist-run spaces that emerged during this same period.

The show is Jayaram’s third Art Week exhibition, and the first to focus on Miami’s artist community specifically.

In the pages to follow, you will find the inspiration and reflections woven between a group of close collaborators and friends. I chose Carlos Betancourt to begin the storytelling because, like the glitter in his work, he has touched nearly everyone in this art community and is a shining guide on the

importance of preservation and archive.

* In Miami, I met Amanda Keeley who was working on a mobile bookstore called EXILE Books and the project evolved into a conversation about books, text, display, and archive. We invited our friend Lizzi Bougatsos, who recently was commissioned by MoMA to compose a sound piece as tribute to John Cage’s 4’ 33”. It was

this addition that opened up the fourth veil and gave meaning to the project in its new home at BFI: Books Fuel Ideas. Every word read or written in delves upon us the poetry / record of human thought. It is why we hold onto our books and share them with others. A lifeline to the threads of history that connect us

across time and space.

– Katerina Llanes, November 12, 2014

prologue

MAKING MIAMI

by KATERINA LLANES - Curator and Program Manager at Jayaram

In my role as Curator for Jayaram, I was thrilled to be a part of conceiving this book, which aims to capture the collective energy of Miami’s contemporary art scene during a pivotal time in our city’s history. I sat and reflected on my own experience as a Miami millennial native, born to Cuban parents and raised in Kendall. In my youth, Miami felt too small for me, and I left the minute I turned 18 for college and then NYC. It wasn’t until I met Naomi Fisher in 2007 that Miami’s secret artworld opened up to me. Naomi was an art star running BFI (Bas Fisher Invitational) out of the Buena Vista building in the Design District. Always a welcoming spirit, Naomi invited me to EVERYTHING and before long, I was tapped in and turned on. I would go on to work at BFI for years, both at the Buena Vista and later at the Downtown ArtHouse that we shared with the TM Sisters, Turn-Based Press and Dimensions Variable. In 2013, I was hired by the Miami Art Museum to run the Time-Based Art program in their new Herzog and de Meuron building, renamed the Pérez Art Museum, or PAMM. These experiences solidified my career as a curator and my new-found love for my hometown.